I was a first-time principal when I first read my state’s kindergarten assessment policy. As a former kindergarten teacher, I had a lot of ideas about what 5-year-olds need to learn when they start school: how to sit in a circle, how to speak nicely to their friends, and that their teachers care. Unfortunately, my state wanted them to spend the first 3 weeks administering four separate and lengthy diagnostic assessments. The kicker? The results of these assessments wouldn’t actually help my teachers understand the needs and academic levels of their newest, youngest students—requiring even more testing to inform actual instruction.

What sticks with me today is the amount of uncertainty around testing: what’s actually required and what is believed to be required; what’s needed to improve instruction and what’s needed for accountability. Too often this confusion leads to unnecessary layers of duplicative assessment. School systems have a responsibility to help school leaders make sense of the testing they’re asked to administer—not just to ensure the right people have the right data at the right time, but to ensure that data needed for decision-making doesn’t come at the cost of student learning.

Right now too much attention is focused on the amount of time spent on test prep and testing (despite the recent news that high-achieving nations test about the same amount as the U.S.). Limiting testing and test prep to arbitrary caps are symbolic attempts, but won’t actually improve the situation in most schools. Instead, we think school systems should pause, identify all the assessments administered in their schools, and engage their educators in a close review of the local assessment landscape. District leadership and teachers should focus on quality – and work together to develop a clear and coherent assessment strategy that ensures the only tests they administer will provide valuable data to inform decision-making and instruction.

Education First spent a year working with district leadership and educators in Syracuse City School District in New York to help the district improve and streamline its assessment program. The goals: Improve the quality of all assessments; eliminate extraneous assessments that do not contribute to teaching and learning; and move toward a better balance of question types across assessments, including performance tasks and high-quality multiple-choice questions. We partnered with Achievement Network (ANet) to create rubrics to help educators look at the quality, alignment to standards and instructional usefulness of local assessments.

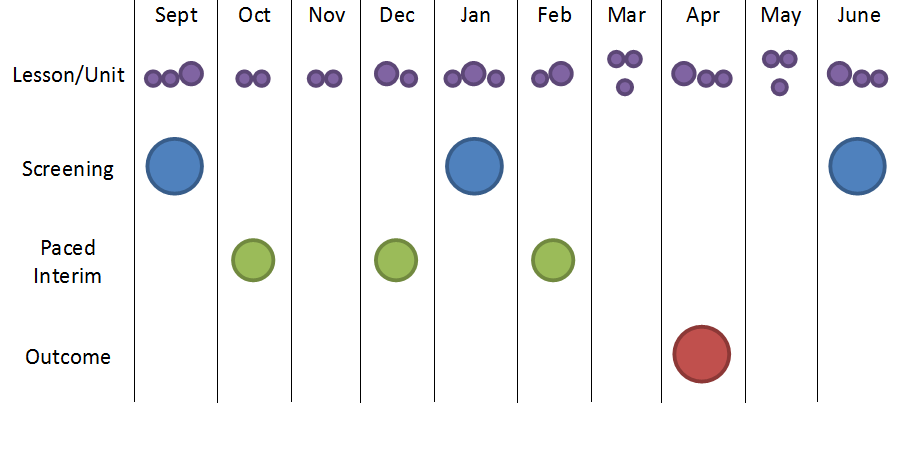

The first step was to identify assessments given in every Syracuse school that covered at least a week’s worth of instruction and was administered by at least two teachers—such as quizzes, diagnostic tests, curriculum unit tests, end-of-course tests, interim assessments and performance tasks. In addition to district-supported assessments like ANet’s interim assessments, the district’s 31 schools identified 63 additional school-based assessments that they administered to students. Of the 63 assessments, schools reported that the majority (52%) were used by an entire subject(s) or course(s) within the school; 42 percent were created by an individual or a team of teachers at the school; 39 percent were used for progress monitoring; and 35 percent were interim assessments. We helped Syracuse educators review these school-created or school-administered assessments and make some decisions about what should be kept, improved or eliminated. Teachers reviewed assessments and recommended, for example, modifying or eliminating the majority of unit tests. As a result of the project, Syracuse district leaders streamlined assessments (for example, eliminating one of two interim assessment systems) clarified district assessment frequency and policy (telling schools, for example, that they don’t need to administer a unit test if there is an interim assessment planned within a week) and developed an overarching framework for assessment. This timeline illustrates Syracuse’s new approach to assessment timing, purpose and use:

We know that many districts and charter management organizations are grappling with the same issues as Syracuse. We created the Fewer and Better Local Assessments: A Toolkit for Educators to take school districts through a step-by-step process of looking at their current suite of assessments, engaging teachers to weigh in on the assessments’ alignment to standards, and making hard decisions about which assessments to keep and which to ditch. The toolkit’s playbook details the steps school system leaders should take, offers lessons learned from our work in Syracuse, suggests common pitfalls to avoid and shares ready-to-use or adaptable tools and materials.

As worthwhile as engaging teachers is, it’s not easy – teachers are busy, and their primary focus has to be their students. To help districts engage teachers at the right level, we and ANet updated the teacher-facing rubrics in Syracuse by testing these with teachers at other schools and creating LASER: Local Assessment Screening Educator Rubrics. We also put together teacher training and other supporting materials, including training materials for LASER and on the process of reviewing assessments, annotated scoring examples for LASER, and assessment literacy professional development materials.

As for my over-tested kindergarteners? After hours of research, I confirmed that the only repercussion of skipping all 4 assessments was a potential school performance score ding should anyone ask for the reports. Losing those points and winning back a month of instruction felt like an obvious choice for me, but probably one I – as a school leader – shouldn’t have had to make. Data are critical to successful instruction, but not when you’re drowning in it. School systems should take the time to select the fewest assessments that will yield the most useful results. This will be no easy task, but increasing instructional time will be worth it in the end. Don’t believe me? Go ask a kindergartener.